This page is a study of three pieces that appear in Gaspar Sanz's guitar method published in 1675 and their relation to flamenco. They are presented here in order of playing difficulty.

Certain styles of popular music from Sanz's era used irregular rhythms that are very similar to those found today in flamenco, although the harmonic tension and release happen at different times and in different ways than in flamenco. The rhythm of Sanz's Zarabanda and Canarios is similar to that of the guajiras and peteneras styles of flamenco, his Jácaras is similar to soleá, and his Pasacalles, if taken in sixes, bears a certain similarity to sevillanas or fandangos de Huelva and, when taken in twelves, can be likened to soleá.

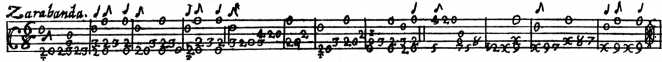

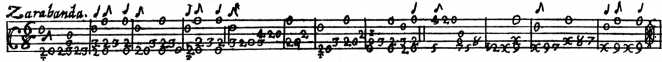

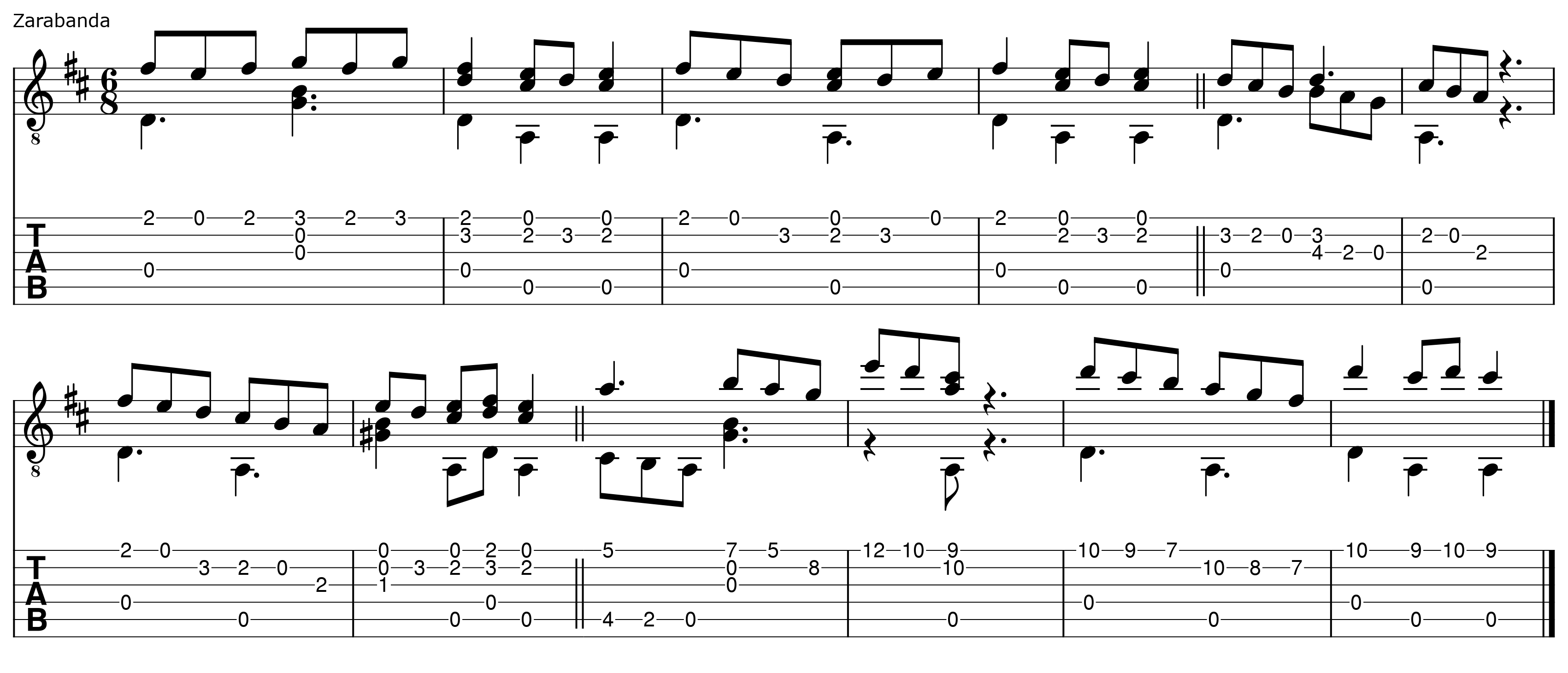

The rhythm of Sanz's Zarabanda and Canarios is often called "de amalgama" in modern flamenco terminology, due to the asymmetrical intervals between the accented beats (3+3+2+2+2). This rhythm is normally written in a mixed meter of 6/8 and 3/4, although it can be found throughout the history of Spanish music, sometimes appearing as a homogenized 6/8 or 12/8, as seen below (the musicologist Dionisio Preciado described this as "camouflaged").

In his 1577 publication "De Musica Libri Septem," the theoretician Francisco de Salinas stated that this rhythm was used in the folk song "Retratada está La Infanta / bien así como solía" and also in the romance "Conde Claros."

The musicologist Eduardo M. Torner wrote that this rhythm is found throughout most of a Christmas carol found in the "cancionero manuscrito de la Biblioteca Columbina" (see the indication below from the work of Emilio Rey García). Written in the early 16th century, the first verse is: "Los hombres, con gran placer."

The musicologist Dionisio Preciado identified this rhythm in number 166 of the "Cantigas de Santa María," although the musicologist Emilio Rey García has suggested that Preciado may have been mistaken, as he based his conclusion on a controversial transcription of Querol. Preciado also indicated the presence of this rhythm in "Paño Moruno" (not Falla's version, but the original from the "Cancionero Murciano"), in another old folk form called the tirana and in certain parts of the Basque ezpata-dantza (banako, binako and laudako).

Emilio Rey García indicates that this rhythm is found in the "Cancionero Musical de Palacio" (compiled around 1520), numbers 12 and 310; in the "Cancionero Musical de la Columbina," numbers 61, 71 and 89 (edition M. Querol); in the "Cancionero Musical de Góngora" (thus named by Querol), numbers 1, 4, 5, 8, 14, 15, 17, 22, 24, 25, 27, 34, 35, 38 and 40; and in 24 pieces included in "Música Barroca Española," also by Querol, appearing in books 32 and 39 of "Monumentos de la Música Española," published by the Instituto Español de Musicología del CSIC.

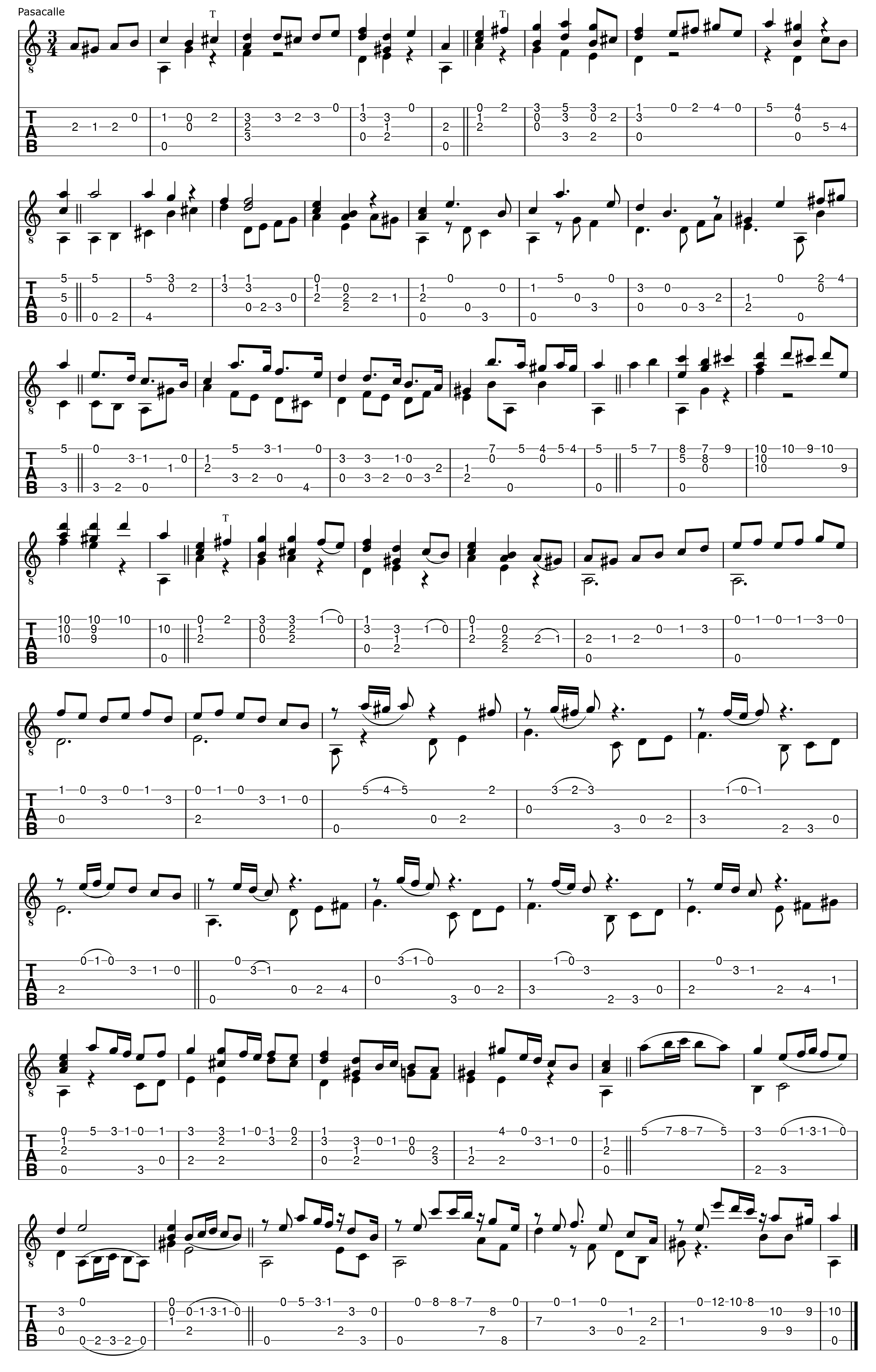

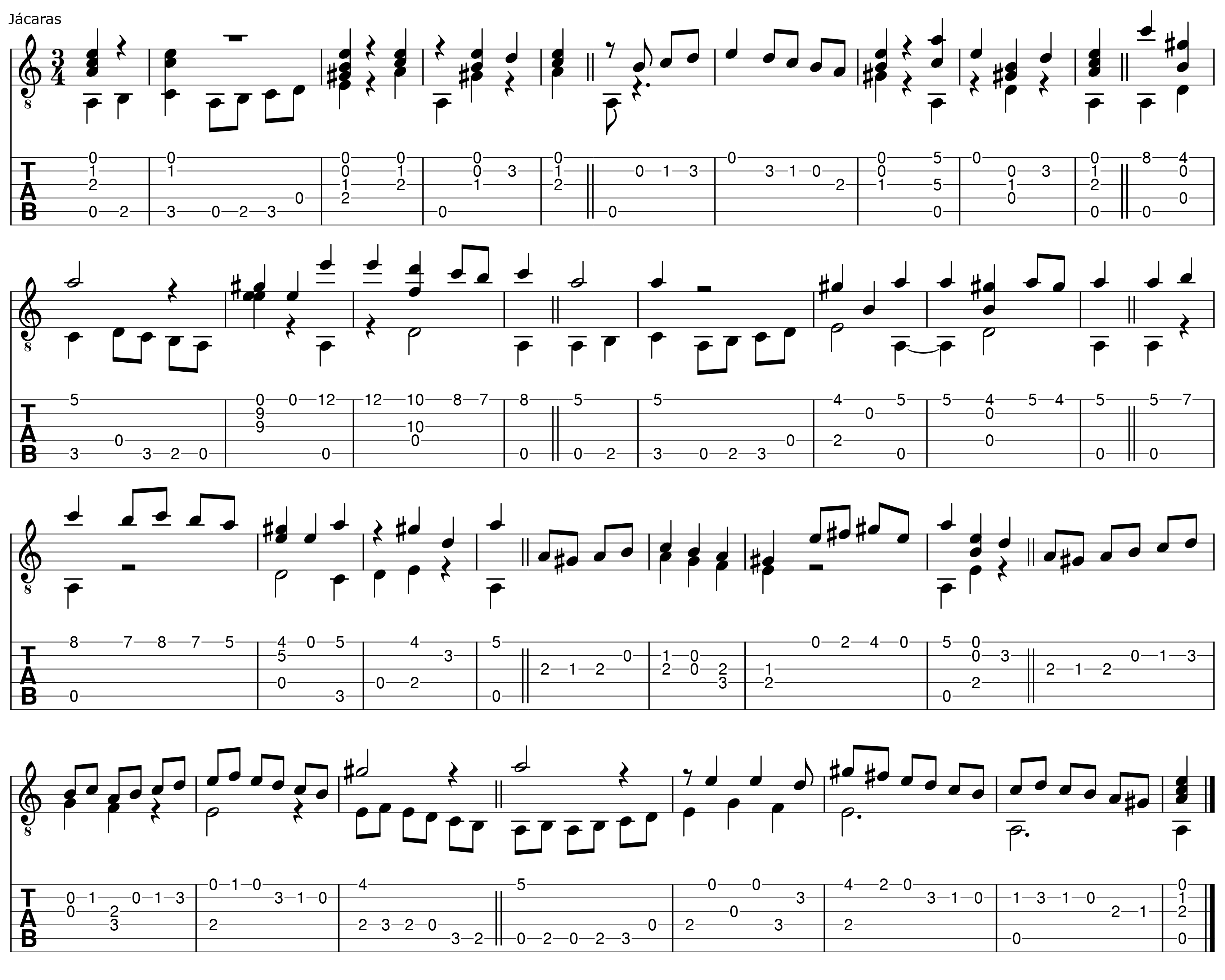

In Sanz's time, the guitar still had only five strings, tuned A-D-G-B-E, basses to trebles. All but the first strings were double string sets (or "courses"), for a total of nine strings. The second and third courses were tuned in unison, and, according to Sanz, the fourth and fifth courses could consist of two treble strings (standard practice in Italy), two bass strings (standard practice in Spain) or one of each. This means that, depending on the instrument, the fifth and fourth courses could be higher in pitch than the third course. Sanz studied in Italy, and his style reflects the tendencies of the Italian school at that time. I've transcribed these pieces from the original upside-down five-string tablature (in which the lower-pitched notes appear on the uppermost lines) to reflect how they sound when played on a modern guitar in standard tuning.

Obviously, the music Sanz wrote was intended to be played on an instrument that was very different from the modern guitar. Because Sanz used trebles for the fourth and fifth strings, playing his music in standard tuning results in octave jumps in certain melodic lines, and some pieces adapt better than others to modern guitar. In some arrangements of Sanz's works, passages on the bass strings have been moved to the trebles for the purpose of maintaining the original melodic line. However, this completely alters the striking-hand fingering, and Sanz apparently put a great deal of importance on this aspect when he wrote the following:

"Great care must be taken in the use of the right-hand thumb. It always plays the lowest voice, and, if there are two numbers, even if they appear on the lowest lines (note: he's referring to the trebles), you should use your thumb for the lowest voice, because the thumb is the finger that has to explain that voice, so that it has more body, and because the second string does not sound as good with an index-finger upstroke as it does with a thumbed downstroke."

Sanz's tablature includes double bar lines that separate passages called diferencias: twelve-beat phrases that are similar in nature to falsetas. In this sense, notice the two-beat pickup measures at the beginning of the jácara and the pasacalle.

The rhythm of this piece, also present in Sanz's "Canarios," is normally written in a mixed meter in 3/4 and 6/8. Apparently, the zarabanda was thought by some to be immoral, as the singing and dancing of this style were prohibited in Spain in 1585 and 1630, respectively. But don't let that stop you from having a good time playing this piece.

This jácara is in the key of A minor and another that appears in the same method is in the key of D minor, such that the two may be likened to the "por arriba" and "por medio" positions of flamenco. Although they are simply popular keys for the guitar, the similarity to soleá is interesting. Beats one to three are assertive and beats four to six follow suit (the pick-up measure helps to center the accents on beats three and six), but here the harmonic tension nearly always resolves on beats six and twelve and is normally maintained for beats eight to ten, unlike soleá, which resolves on beat ten. Try counting the soleá rhythm while listening to the audio file. Notice that the sixth diferencia has only 11 beats, which sets up the conclusion of the piece in cycles that start on beat 12, as in the pasacalle.

This piece, presented by Sanz as an exercise for loosening up both hands, makes for an excellent workout in rest strokes. Several left-hand effects, such as mordents, vibrato and trills (T), are only partially represented in the transcription. Sanz stated that, as a general playing rule, the thumb, index and middle fingers should be used whenever possible. The fingering in the last diferencia is worth special attention. In the third staff, we can see echoes of an idea in thirds that Montoya and Melchor often played in soleá. The music below is composed in twelve-beat passages, similar to the jácara. Interpreted in sixes, certain moments may be likened to sevillanas or fandangos de Huelva. Notice that, like the jácara, the passages start with a well-defined 1-2-3 and that, toward the end, the cycles begin on beat 12, which adds a flowing sensation to the conclusion.